#6. Why science works?

The core principles that make scientific approach effective, or surprising nature of wrinkly fingertips

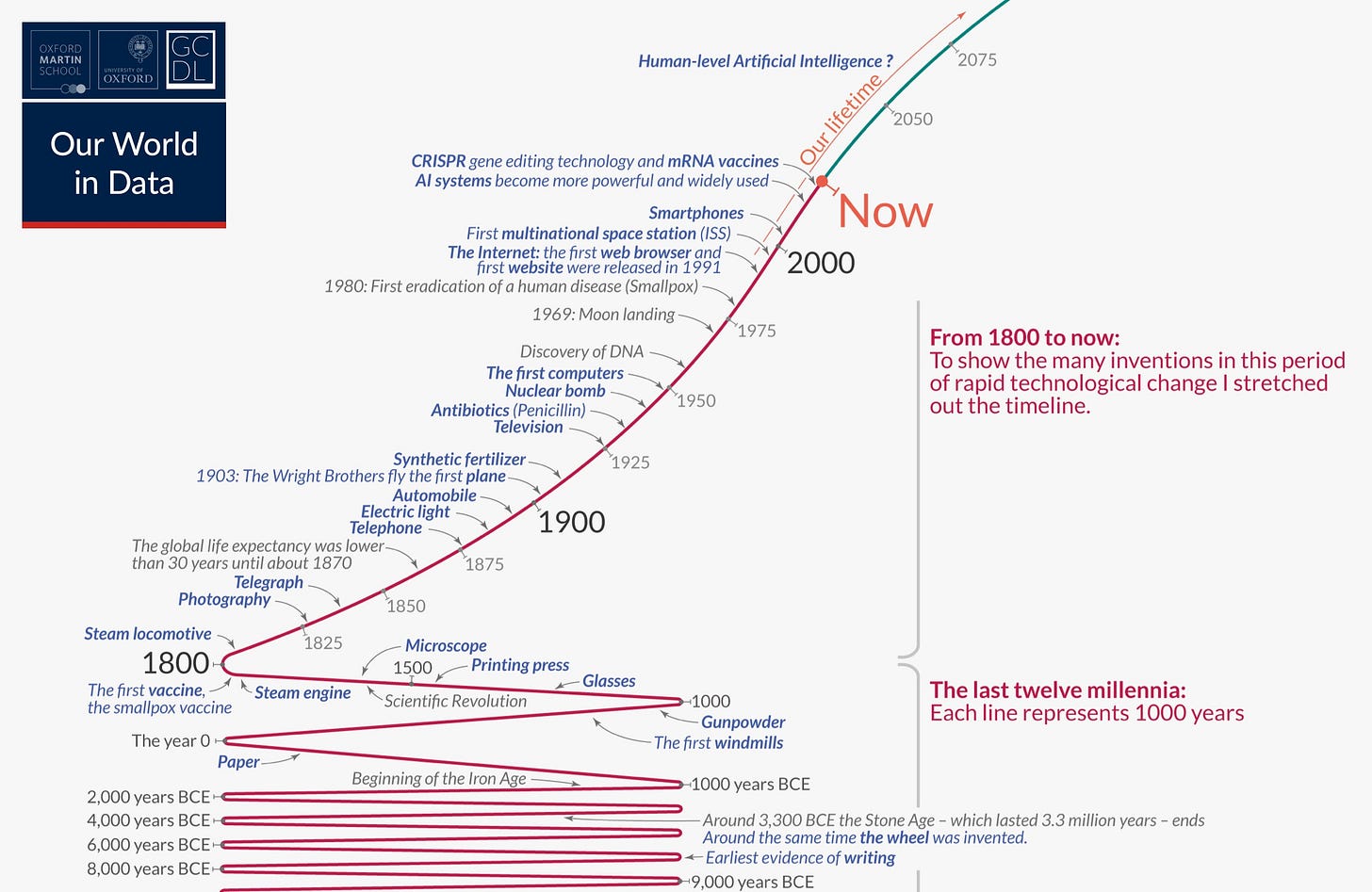

If you look at the timeline of technological progress of our civilization, it shows a tremendous exponential growth over the last 200 years, which is just a flash next to the 200,000-year-long history of the Homo sapiens1 species, who had started with no more than rocks and fire.

While most of these developments were put in practice by engineers and entrepreneurs, it’s the fundamental scientific research that made those advances possible in the first place. For example, there would be no steam engine and later combustion-engine cars without the formulation of fundamental laws of thermodynamics first. There would be no microscopes and later photography without scientific formulation of the laws of optics. There would be no telephone and later computers and smartphones without the scientific formulation of electricity. No GPS2 without general relativity. The list can go on and on, with all the scientific works and industrial applications tightly intertwined into a series of small advances and groundbreaking discoveries, which ultimately have led us to the current state of technological development.

💡 This level of development is so high that it can seem absurd at times. Like when you check the Weather app on your phone, which sends GNSS signals to the satellites orbiting the Earth, to determine your location, then requests the aggregated data from a dozen of weather stations and processed by multiple servers, sending it back to you over a series of optical fibers and radio transmitters to eventually show you a number and an icon 🌦️ on the screen.

All this when you could just stand up and look out the window 👀

There are a few core principles that scientific approach is based on, which make it so effective at gradually building knowledge across decades and centuries. In the following I will talk about those principles, as I see them based on my own academic experience.

1. Verifiable Answer

The very first requirement for any kind of question to be scientific – it must have an objectively verifiable answer. Usually it’s some aspect of the world that we’re trying to understand, approaching it with a specific discipline that is best equipped for that specific question (physics, chemistry, biology, psychology, mathematics, etc.) Regardless of the discipline, the answer to the question must already be embedded in the world itself such that the reality becomes the ultimate judge. Example scientific questions can be:

What makes objects fall on the ground?

Why the sky is blue?

Why fingers get wrinkly under water?

💡 Answer to the last question is at the end of this article, and it might surprise you!

Scientific approach to answering such questions has essentially 3 steps:

make a hypothesis about what the answer would be → potential answer;

develop it into a theory, using logical reasoning, to describe all practical implications of that hypothesis → theoretical predictions;

verify that all these predictions agree with reality at all times → experimental observations.

Step 3 is what separates science from philosophy, which addresses questions that are rather general or abstract, and therefore unverifiable. Philosophical questions don’t have one objectively true answer. Instead they can have multiple answers (like hypotheses) that can be quite elaborated with logical reasoning (like theories), but there is no way to tell if any particular answer is actually true. Ultimately success of a specific philosophical idea is determined by how many people know about it and whether they approve it. This leaves plenty of space for ego, authority, influence and other human factors, which are very much restricted in science.

💡 I would say that philosophy is actually closer to politics or marketing than it is to science, so it’s quite ironic that the academic degree given to doctoral candidates in scientific disciplines is still called “PhD” (Doctor of Philosophy). Considering how far science has gone from philosophy, that name should have been changed to something like “Doctor of Science” long ago. But people don’t like changes and often choose familiarity over common sense, especially if they are not scientists.

This requirement to be experimentally verifiable limits the list of questions or answers that science can seriously consider. For example, imagine a hypothesis that gravity is caused by a big monster inside the Earth pulling objects down by invisible strings. To prove it you’d need to dig a very deep hole and find that monster. If you have no technical capability to do that, then considering this hypothesis is pointless, since there is no way to verify it. Therefore, you lower the ambition of your question to something more practical, like “How fast do objects of different sizes, shapes and materials fall down?“ or “How does the falling speed depend on the height?“, etc. These are more specific questions for which predictions can be made and verified through experiments, to eventually converge to a theory that is able to make correct predictions for all these situations.

Now, after studying these very specific questions we’ve developed a very elaborated theory of gravity that explains way more effects than the underground monster could ever explain. Therefore, now we can say with absolute certainty that there is no way it’s because of a monster inside the Earth, without the need to dig underground.

2. Respect for Skepticism

Step 3 – proving that all theoretical predictions of the theory match the reality, is practically impossible, since there is usually an infinite number of situations for which the predictions can be made and tested. Therefore, scientists do the opposite – they assume that the theory is right and then try to prove it wrong by strategically choosing specific cases that challenge its predictions.

Only if the theory passes these tests every single time, such that scientists run out of any new meaningful cases to challenge it, only then they consider it to be a valid theory that can be trusted and built upon. Nevertheless, a bit of skepticism always remains in the back of every scientist’s mind, because at any moment some new experimental evidence can appear that contradicts that theory prediction, meaning that something in it is still missing.

What’s important is that as soon as a contradiction is found, it doesn’t matter any more how successful the theory has been before or how respected and influential the authors of the theory are. A single experimental evidence will prove it wrong, because it’s not someone’s subjective opinion, but an objective truth revealed by the nature itself.

This is the fundamental difference of science from religion, which is built on belief, seeing skepticism as a weakness. A perfect example of that is the famous trial of Galileo Galilei3 for his heliocentric theory, suggesting that Earth orbits around the Sun and not the other way around. This was seen as a heretical contradiction to the Holy Scripture by the Catholic Church, which insists on humans and the Earth being the central figures in the Universe.

3. Precision of the Language

As science relies heavily on comparison between theory and experiment, it is critical that apples are compared to apples, meaning that what is observed and what is predicted must be exactly the same. This is achieved by a rigorous use of language, with precise definitions of any special terms, elaborated description of all the conditions and effects being considered. Before publishing a scientific paper, every sentence is questioned by the authors for the possibility to sound ambiguous.

This minimises the possibility of misinterpretation by any other scientists who might want to challenge it or build on top of it in the future. This is also why mathematical language plays such an important role in most of the scientific disciplines – numbers, graphs and formulas provide much less room for misunderstanding than words.

Another manifestation of precise language lies in the way results are formulated in scientific publications – they precisely describe the exact thing that was predicted or measured. Any further speculative guesses or logical implications are clearly stated as the author’s personal opinion rather than an objective fact, such that others can decide how skeptical to be about it.

💡 The title of my PhD thesis was: “Associated top-quark-pair and b-jet production in the dilepton channel at sqrt(s)=8 TeV as test of QCD and background to tt+Higgs production“. It had 60+ pages of detailed explanation of all the aspects of my analysis (what and how has been measured), and only 3 pages with the actual results (plots and numbers).

This precision of the language also doesn’t let science talk about things that go beyond its reach, like, for example, whether our world was created by god. Science can tell us with a high degree of confidence how long humans have been around, how old our planet is, and based on how the universe is behaving – that it must have started from The Big Bang. It can even tell roughly how long ago it happened, and we can even detect the light that was produced at that moment4, but what was before that – we have no way to know, as there was neither space nor time before the Big Bang, according to our current understanding. Therefore, no matter what idea you have about the reason behind the Big Bang, for science it doesn’t matter because all of them are equally unverifiable.

It’s not excluded though that in the future our knowledge will advance to the point where that kind of question will become scientifically meaningful. But for now it is just a speculation that belongs to philosophy or religion, but not science.

4. Consistency in Every Detail

If two independent groups of scientists perform exactly the same experiment to measure exactly the same thing, in theory they should obtain exactly the same result. In practice though this is nearly impossible, because there are tons of tiny details that will inevitably be different between any two experiments. These can be the model or calibration of the instruments, fluctuations in the electric power line, slight differences in the room temperature or humidity, etc. All the tiny factors add up, potentially leading to noticeable differences in the final results.

This is why we look not for exact equality but for consistency between different results. This requires the result (R) to include not only the measured value (V) but also its uncertainty (ΔV), which accounts for all the known sources of variations.

In fact, sometimes more time is spent evaluating the uncertainty than performing the measurement itself, yet it is absolutely necessary for being able to tell if any two results are consistent or not. There is an elaborated mathematical apparatus for saying how compatible any two results are, which always boils down to numbers – the most precise language we have. And at no point something that looks inconsistent can be explained with just a “boh“5 🤷🏻. It can only mean a mistake in the experiment or the theory, which must be resolved.

A chain of such theoretical predictions and experimental measurements that are always consistent between themselves is what allows science to gradually add deeper and deeper layers of understanding, keeping this massive structure of knowledge stable and functioning across centuries of documented research.

Instead, inconsistencies are usually what drives major discoveries, forcing scientists to come up with deeper theories explaining the reality in more situations than before. Without very precise language and very tight consistency requirements at each point, it would very quickly become “roughly right“ in every situation, leaving no actual inconsistencies to resolve.

5. Peer Review

The last important step relies on scientists checking the work of other scientists. In particular, this is part of the review process before an article gets published in a scientific journal. In any serious journal there is a pool of scientists – “reviewers“, who get to critically review every article submitted for publication, checking if it satisfies all the necessary quality criteria:

be scientifically meaningful and new compared to everything that has been published before;

provide clear and precise documentation with no ambiguities;

be consistent with existing publications on the same topic (or explain the inconsistencies).

Usually one article is reviewed by several independent people from different institutions, each of whom is an expert in the relevant field and submits a list of comments about every single detail in the article that is not fully clear or convincing. The original authors then have to address each comment by providing explanations, improving the text of their article or including additional calculations or measurements proving that their results are actually correct.

💡 Many journals adopt special anonymity policies, hiding the names of the authors from the reviewers and vice versa. This reduces the chances of prejudice or conflict of interest during the peer-review process, making it more likely that all publications are evaluated only based on their scientific quality and value.

Quite often a single article goes through multiple rounds of such exchanges between reviewers and authors, which can take months or even years until all the reviewers are satisfied. Only then the article is allowed to be published, becoming available to the wider audience, who can read it, discuss it at scientific conferences or use it as inspiration or reference for new studies.

Surprising inconsistency of wrinkly fingers

Here is a peculiar example of an inconsistency revealing a deeper scientific knowledge – the mystery of wrinkly fingertips.

We all know how the tips of our fingers get wrinkled if we keep them under water for a while, for example in a bath-tub or in the sea. The most intuitive hypothesis for this effect would be that it must be the water somehow getting soaked under the skin and making it wiggly. It also seems reasonable to assume that it must be the combination of the hard skin and the soft tissue underneath that is responsible for this effect.

If you consider other parts of your body that have soft tissue, like your buttocks, cheeks or ear lobes – no wrinkling happens there, as it’s covered by soft skin. Same situation with the rest of the body, where you have just soft skin and no soft tissue at all. The only parts where you do have soft tissue under hard skin are your hands and feet, which both get wrinkled.

If you look at it as a philosopher, applying only logical thinking, you could declare this case solved, since logically everything matches perfectly. But if you look at it as a scientist, you’d perform experiments to prove your hypothesis. You’d put hundreds of people’s hands under water and sure enough, every time you would see the tips of their fingers get wrinkled. Following the principle of precise language, you’d have to measure at least one parameter that can be expressed numerically – for example, the time it takes the wrinkles to appear for each person.

What you’d probably see is that it’s not the same for everyone, so you’d have to do it more systematically. You’d document all the possible variables that could potentially have an influence on the wrinkling time, related to both the skin (thickness, oiliness, age, colour, etc.) and the water (temperature, acidity, concentration of chemicals, like salt or chlorine, etc.) As you go on with this experiment, collecting thousands of data points, you might start seeing some correlations and eventually develop a theoretical model that can predict how long it would take the wrinkles to appear for a given person in a bath tub with a specific water at a specific temperature. I don’t know if such a model would have any practical value, but in principle it’s possible.

What all these experiments would do is that they would add more details to the theory of wrinkled fingers based on the initial hypothesis – that it’s the combination of soft tissue + hard skin + water causing the skin to wrinkle. Yet none of them would prove the initial hypothesis to actually be true, since there is always room for skepticism.

💡 The initial hypothesis implies that there must be some unknown physical or biological effect in action. What if it’s the same effect that causes fresh paint on metal to wrinkle and chip away after hot-summer rain? This could be a good reason to study wrinkled fingers further and potentially discover a new way to make paints more water-resistant.

Eventually a single inconsistency ❌ in a very rare case proved this initial hypothesis wrong. It happened when the same experiment was repeated on a person with a kind of damage to the nervous system that interrupted any sensory input from their hand. In that case wrinkles did not appear, no matter how long their hand would stay underwater. That was a paradigm shift, since now it can’t be just the water itself making the skin wrinkle, but our brain commanding it to do so when it senses the presence of water.

At this point a completely new set of questions can be asked to understand it further. Is it conscious or subconscious? Does it depend on the mood of the person? Can it be caused by a dream during sleep, without any actual water in action? Finally, why on Earth would our brain send such commands in the first place?

A widely-adopted possible answer to the last question is that wrinkles noticeably improve grip on wet surfaces, making it easier to grab smooth objects under water and safer to walk over wet rocks, feeling less slippery. Since we barely ever use that advantage in our everyday life, it’s hard to imagine why that feature would be present in DNA of all the people on Earth. A speculative explanation for that is that it’s a very old remnant feature that we’ve inherited from reptiles, who spent way more time in water. The fact that some monkey species also develop wrinkles in the same way fits this hypothesis in the evolutionary context, but of course it’s not enough to really prove it. As scientists we would need way more evidence and zero contradictions to eventually accept it as a mainstream theory.

💡 If you’re curious to know more, this BBC article provides a great overview of the different studies about this peculiar phenomenon and many cool aspects that have been discovered along the way, including the potential for early detection of Parkinson’s disease.

Epilogue

There are obviously way more aspects and nuances to a scientific process, which also appear differently in various scientific disciplines. But the core principles I’ve discussed above are the most important and universal, I think.

It’s important to note that these are the principles of science as a discipline, not necessarily of a scientist as a human. Any given scientist, being susceptible to the same kind of biases or character flaws as anyone else, can potentially deviate from these principles. Yet the rigorous system of science is meant to minimise their damage, while scientists are trained to be fully aware of such risks at all times.

I would say that these principles are followed most effectively in fundamental research, where the main objective is to simply discover the truth. Conflicts of interest and consecutive biases arise more often in applied research, which inevitably is connected to someone’s interests, which also have more influence on the funding. A prime example of these scientific principles being violated can be found in pharmaceutical research, as has been described quite well in this article by MIT Press:

In 2010, the NIH (National Institute of Health) found that studies with significant or positive results were more likely to be published than those with non-significant or negative results and tended to be published sooner.

So even science can get messy when people get involved, but I would blame it on people rather than science.

In fact, the more appropriate abbreviation is GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System), while GPS is just a specific implementation of this concept in US, who were the 1st to deploy it and became more known, Wikipedia

“Boh“ is a common Italian expression, meaning “I don’t know“, Wiktionary